The Champ and the Shadow: Sugar Ray Leonard’s Comeback in Worcester, 1984

Photo credit: Joe Daly, 2024

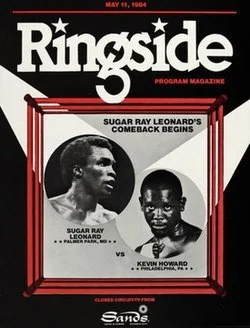

By the time Sugar Ray Leonard stepped into the ring at the Worcester Centrum on May 11, 1984, the city’s largest indoor arena pulsed with a volatile cocktail of pride, tension, and cautious optimism. Worcester, known more for its industrial grit and underdog determination than as a boxing mecca, had improbably become the site of one of the most intriguing comeback fights in modern boxing history. Leonard, the sport’s golden boy, Olympic hero, and former welterweight champion, was returning to the ring after a two-year hiatus. The opponent? Kevin Howard, a scrappy, unheralded pug from Philadelphia whose reputation oscillated somewhere between "tough journeyman" and "guy you call when no one else picks up."

For a sixteen-year-old kid growing up in Worcester, the chance to see Sugar Ray Leonard fight in person was nothing short of miraculous. My father had scored the tickets through one of his Irish buddies — a wiry, fast-talking character with a knack for finding himself in the middle of anything remotely interesting. This time, he’d somehow gotten involved in the fight’s promotion, greasing the right palms or calling in favors from God knows where. However it happened, we found ourselves in possession of two golden tickets to see one of the greatest fighters of all time return to the ring.

Boxing in 1984 was an entirely different animal. It wasn’t the niche, pay-per-view circus act it has become. Back then, the sport was omnipresent, beaming into living rooms on network television every weekend. The names of the champions—Ali, Frazier, Foreman, Holmes, Hagler, Leonard — weren’t just known to fight fans; they were stitched into the fabric of American culture. These men were larger-than-life icons, simultaneously gladiators and celebrities. For a working-class kid, sitting in the Worcester Centrum to watch Sugar Ray Leonard’s comeback wasn’t just cool — it was transcendent. It was like watching Michael Jordan lace up for a pickup game at your local gym or Springsteen deciding to play an impromptu set in your buddy’s garage.

What unfolded that night wasn’t the storybook triumph I’d envisioned, but it was something far more electric—a reminder of boxing’s raw, unpredictable theater and its ability to reflect the human condition in all its flawed, messy glory.

Leonard wasn’t just a fighter; he was a cultural phenomenon. By 1984, he’d already achieved boxing immortality with victories over legends like Wilfred Benítez, Roberto Durán, and Thomas Hearns. His dazzling speed, balletic footwork, and charismatic smile had made him the darling of Madison Avenue and the face of a sport in desperate need of a new icon after Muhammad Ali's decline. Yet, in 1982, Leonard was forced into premature retirement due to a detached retina, an injury that threatened to end his career and possibly his eyesight.

The comeback was audacious, perhaps reckless. The boxing world had doubts — not about Leonard’s skills, but about his physical integrity and his motivations. Was this about legacy, or just vanity? And the journey that brought Sugar Ray Leonard’s comeback to the Worcester Centrum was as winding and unpredictable as a heavyweight slugfest. Initially, Leonard had set his sights on Madison Square Garden, the hallowed ground of boxing lore, to stage his grand return. However, the rock band Yes had already booked the Garden for February 25, forcing Leonard’s team to consider other venues. Ironically, Yes later canceled their concert due to illness, and the Garden became available. But by then, Leonard’s lawyer and adviser, Mike Trainer, had pivoted to Atlantic City, securing a deal for the fight there.

Yet even Atlantic City wasn’t destined to host the event. New Jersey’s exorbitant 9% luxury tax on ticket sales turned out to be a dealbreaker, sending Leonard’s team scrambling once again for an alternative. Enter the Worcester Centrum, a scrappy, unassuming venue far from the bright lights of New York or the glitzy casinos of the Jersey Shore. Trainer struck a deal with Worcester, whose 14,000-seat arena offered lower overhead and a guaranteed enthusiastic crowd. The decision was pragmatic rather than glamorous, but it gave the fight an unexpected charm—a star-studded boxing match staged in a working-class city that rarely hosted such marquee events.

For Worcester, it was a chance to shine on the national stage. For Leonard, it became the backdrop for a comeback story that would prove far more complex than he—or anyone else—had anticipated.

Kevin Howard, meanwhile, was nobody’s golden boy. His record stood at a respectable 20-4-1, but he’d lost two of his last three fights and wasn’t expected to challenge a fighter of Leonard’s caliber. Dubbed "The Spoiler," Howard’s main credential was his toughness. He wasn’t supposed to win. He wasn’t even supposed to make it interesting. He was there to play the patsy, a warm body to ease Leonard back into the sport.

When the bell rang, it became clear Leonard had miscalculated. The local fans, many of whom had shelled out $25 — a king’s ransom in 1984 dollars — expected a coronation. What they got was a war. Howard came out swinging, throwing bombs as if he’d spent the last six months mainlining Marvin Hagler highlight reels. His aggression caught Leonard off guard, forcing the former champ into a defensive shell.

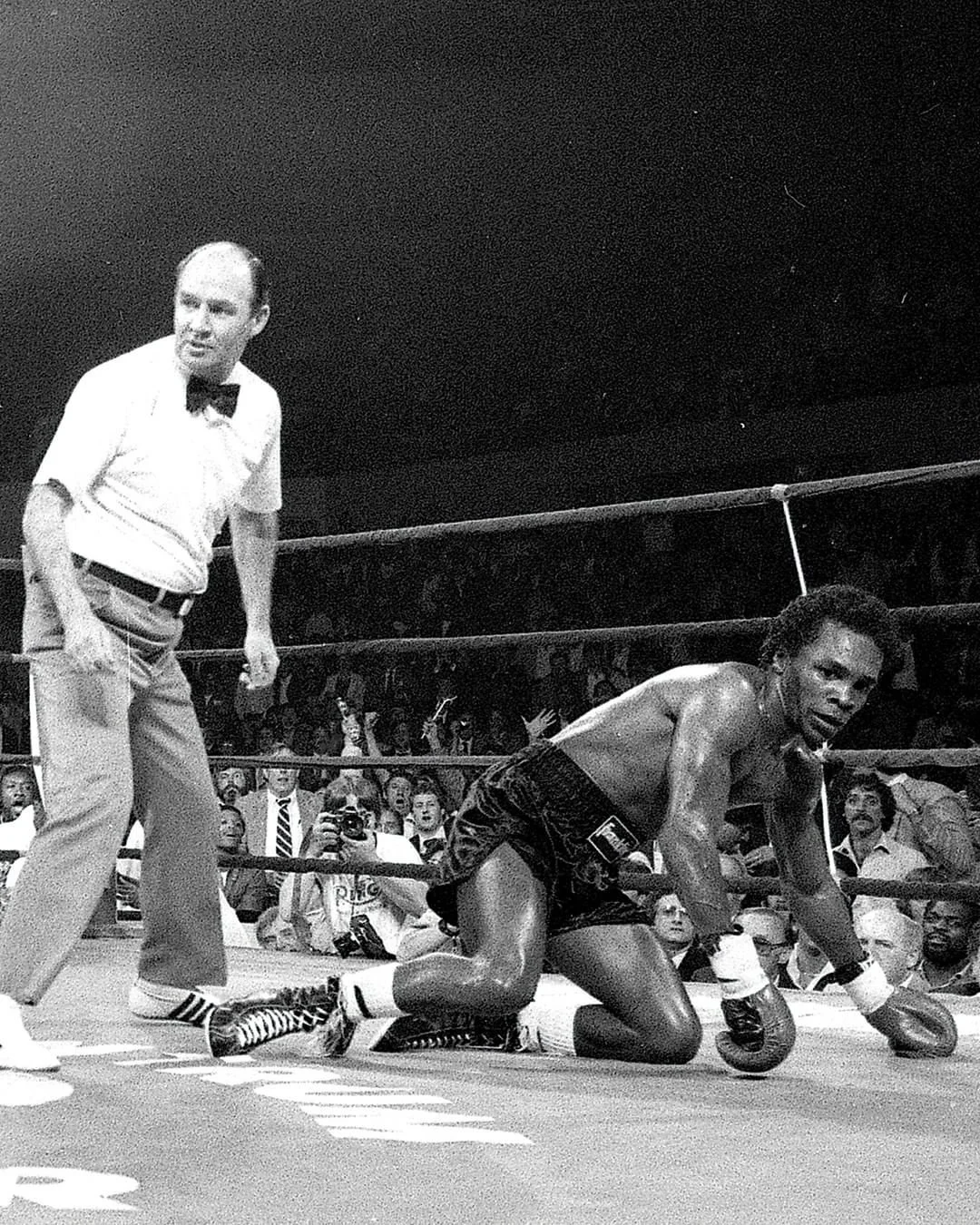

By the fourth round, the crowd’s jubilation had turned to murmurs of unease. Leonard’s timing was off, his punches lacked snap, and Howard’s relentless pressure was starting to pay dividends. In the fourth, Howard delivered the unthinkable—a right hand that sent Leonard sprawling to the canvas. For a brief, agonizing moment, the world stopped. Sugar Ray Leonard, the untouchable golden boy, was on his back.

The knockdown was a wake-up call. Leonard’s ego, long dormant, roared to life. From the fifth round on, he fought with a mixture of desperation and artistry. He danced, he jabbed, he landed combinations that reminded everyone why he was once the best in the world. By the ninth round, Howard was out of gas, his face a mask of sweat and blood. Leonard seized the moment, delivering a flurry of punches that forced the referee to step in and end the fight.

Leonard had won by ninth-round TKO, but it was a Pyrrhic victory. The knockdown became the story, overshadowing the result. The critics were merciless. “Rusty,” “arrogant,” and “reckless” were just some of the kinder adjectives thrown around by sportswriters in the aftermath. Leonard himself seemed shaken. In the post-fight interview, he admitted the knockdown had humbled him. “I wasn’t as ready as I thought I was,” he confessed. The Worcester experiment had been a calculated risk, and while he emerged with his hand raised, his invincibility was forever tarnished.

Howard, for his part, became a cult hero. The knockdown of Leonard was a career-defining moment, elevating him from anonymous journeyman to trivia-night legend. Though he would never again fight on such a grand stage, his performance earned him a measure of respect that eluded many fighters with shinier records.

Leonard’s victory marked the beginning of an on-again, off-again relationship with boxing that would define the latter half of his career. He returned in 1987 to defeat Marvin Hagler in a controversial split decision that remains one of the sport’s most debated fights. But the ghost of Kevin Howard—the night Sugar Ray hit the canvas—would linger in the background of his story.

For Worcester, the fight was a brief moment in the spotlight, a chance to play host to a clash of narratives: the fallen hero versus the underdog with nothing to lose. The Centrum, usually reserved for minor league hockey and traveling circuses, had become the center of the boxing universe for one night. And while the city may not have cemented itself as a boxing hub, it can forever claim to be the place where Sugar Ray Leonard rediscovered his humanity.

In the end, the Leonard-Howard fight was more than just a boxing match. It was a microcosm of the sport itself—an arena where hubris meets reality, where reputations are built and shattered in the blink of an eye. For Leonard, it was a cautionary tale. For Howard, it was a chance to punch his way into history.

And for me, my dad, and the city of Worcester, it was a gritty, glorious night under the lights.